With recent revelations of shenanigans within our national parliament, our noble leaders, mostly men, have been in the limelight. Bad behaviour and political bumbles aside, it is interesting to note that the image of leadership that male (that is most of them) parliamentarians still adhere to depends on a rigid, archaic dress code. The formal dress for men has hardly changed for about a hundred and fifty years, except for a brief flirtation with colour and caftans in the nineteen-sixties and seventies.

Our Prime Minister occasionally wears bright-coloured caps and sports wear, and a previous one was seen dressed in lycra, but it’s obvious that our noble leaders quail at the thought of appearing in the hallowed halls of government wearing anything but a suit and tie. Even the colour of their ties is open to comment. Have people forgotten that a South Australian premier once wore pink shorts to parliament? ‘Hot pants’ the shocked press called them, but that was in the seventies, when men briefly dared to rebel.

Women in advanced countries like Australia long ago threw off the gender-based dress restrictions that had been imposed on them for centuries. Basically, we can wear whatever we like, bikinis, mini skirts, maxi skirts, daring décolletages, jeans, shorts, even the man-style dark suit. It has been accepted that women could wear pants in public for almost a century. Only our personal body image inhibits us.

So, what is it with men and clothes? Are they so unsure of their maleness that they must hide behind the uniform of masculinity? Must a man prove his gender by wearing trousers and jacket in funereal colours, with the archaic and unnecessary necktie?

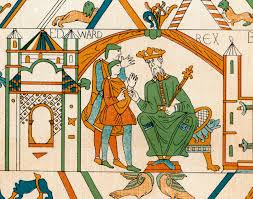

Look back at history. Male rulers and heroes did not wear suits and ties. From early times, they mostly wore some form of skirt. In mediaeval illustrations of kings being crowned, you’ll find them wearing robes – long dresses. Still worn in the Middle East as it was in biblical times, the robe was the ceremonial dress for many rulers and still is for the Pope and other Christian leaders.

But it was not just pharoahs, emperors and kings. European peasants wore tunics, as did Roman legionaries and Assyrian warriors. Ancient Egyptian soldiers, like the hardy, warlike Scottish highlanders, wore kilts.

Why is it that so many brides want to dress their grooms in the kilt that a whole clothing hire industry has grown up to provide Highland dress outfits for weddings? Possibly as a result of the popular Outlander stories, the kilt still carries a hint of its romantic, swashbuckling history.

But it wasn’t just the style of male clothing. Look at images of the kings of England and other European countries. Up until the late nineteenth century, you will find them wearing silks and satins, velvet and lace. Except that they could show off their legs in tights if they were young and shapely enough, they were as frilly as the women. In fact often they outdid their womenfolk.

King George III

Charles I -before he lost his head!

And a happy, laughing cavalier

These men weren’t all transvestites or transgender. Many kings, and even popes, proved their maleness by fathering several children in and out of wedlock. Neither were they sissies. Some were the most famous heroes of history.

No, wearing these expensive materials was a status symbol. Ordinary folk couldn’t afford fancy cloth. There were even Sumptuary Laws, at one time, prohibiting the wearing of such materials by any but the nobility. And in Ancient Rome only the emperor and high nobles could ‘wear the purple’ because the purple dye, made from a substance secreted by a type of sea snail, was extremely expensive. At one time it was worth its weight in gold.

I can’t see satin and lace coming back into fashion any time soon, but perhaps our male leaders could start a trend and set an example for the rest of their sex.

Loosen up guys, live dangerously and get a bit of colour into your lives. Find the courage to throw away the stuffy old dress code and you might even be able to jettison those archaic, misogynistic attitudes that keep talented women out of the upper echelons of power.